Posts Tagged: modeling

Paper: Arithmetic with Arabic vs. Roman numerals

| … how information is represented can greatly affect how easy it is to do different things with it. (…) it is easy to add, to subtract, and even to multiply if the Arabic or binary representations are used, but it is not at all easy to do these things — especially multiplication — with Roman numerals. This is a key reason why the Roman culture failed to develop mathematics in the way the earlier Arabic cultures had. |

| D Marr (1982): Vision, p. 21 |

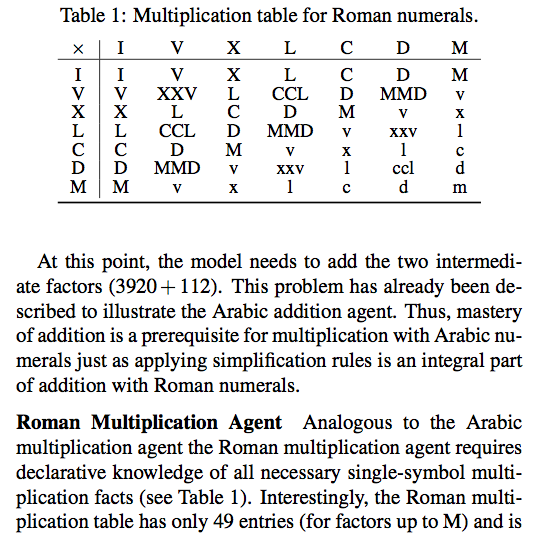

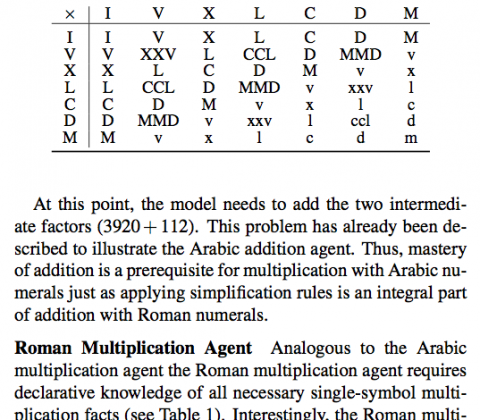

Dirk Schlimm, Hansjörg Neth

Modeling ancient and modern arithmetic practices: Addition and multiplication with Arabic and Roman numerals

Abstract: To analyze the task of mental arithmetic with external representations in different number systems we model algorithms for addition and multiplication with Arabic and Roman numerals. This demonstrates that Roman numerals are not only informationally equivalent to Arabic ones but also computationally similar — a claim that is widely disputed. An analysis of our models’ elementary processing steps reveals intricate trade-offs between problem representation, algorithm, and interactive resources. Our simulations allow for a more nuanced view of the received wisdom on Roman numerals. While symbolic computation with Roman numerals requires fewer internal resources than with Arabic ones, the large number of needed symbols inflates the number of external processing steps.

Paper: Discretionary interleaving and cognitive foraging

| (…) we make search in our memory for a forgotten idea, just as we rummage our house for a lost object. In both cases we visit what seems to us the probable neighborhood of that which we miss. We turn over the things under which, or within which, or alongside of which, it may possibly be; and if it lies near them, it soon comes to view. |

| William James (1890), The Principles of Psychology, p. 654 |

Stephen J. Payne, Geoffrey B. Duggan, Hansjörg Neth

Discretionary task interleaving: Heuristics for time allocation in cognitive foraging

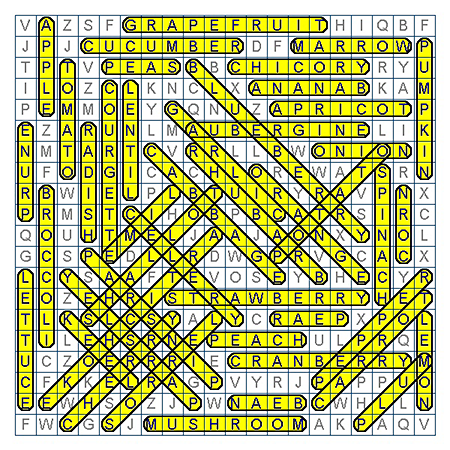

Abstract: When participants allocated time across 2 tasks (in which they generated as many words as possible from a fixed set of letters), they made frequent switches. This allowed them to allocate more time to the more productive task (i.e., the set of letters from which more words could be generated) even though times between the last word and the switch decision (“giving-up times”) were higher in the less productive task. These findings were reliable across 2 experiments using Scrabble tasks and 1 experiment using word-search puzzles. Switch decisions appeared relatively unaffected by the ease of the competing task or by explicit information about tasks’ potential gain. The authors propose that switch decisions reflected a dual orientation to the experimental tasks. First, there was a sensitivity to continuous rate of return — an information-foraging orientation that produced a tendency to switch in keeping with R. F. Green’s (1984) rule and a tendency to stay longer in more rewarding tasks. Second, there was a tendency to switch tasks after subgoal completion. A model combining these tendencies predicted all the reliable effects in the experimental data.

Paper: Melioration dominates maximization

| There is no reason to suppose that most human beings are engaged in maximizing anything unless it be unhappiness, and even this with incomplete success. |

| R.H. Coase (1980), The Firm, the Market, and the Law, p. 4 |

Hansjörg Neth, Chris R. Sims, Wayne D. Gray

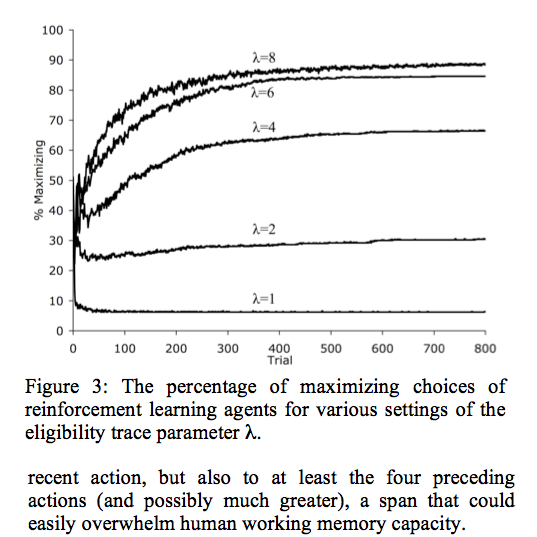

Melioration dominates maximization: Stable suboptimal performance despite global feedback

Abstract: Situations that present individuals with a conflict between local and global gains often evoke a behavioral pattern known as melioration — a preference for immediate rewards over higher long-term gains. Using a variant of a binary forced- choice paradigm by Tunney & Shanks (2002), we explored the potential role of global feedback as a means to reduce this bias.