Posts Tagged: feedback

issues of feedback, learning from feedback

Paper: Melioration as rational choice

Melioration (…) is the dynamic process controlling allocation of time across response alternatives.

Herrnstein & Vaughan (1980). Melioration and behavioral allocation, p. 143+172

Chris R. Sims, Hansjörg Neth, Robert A. Jacobs, Wayne D. Gray

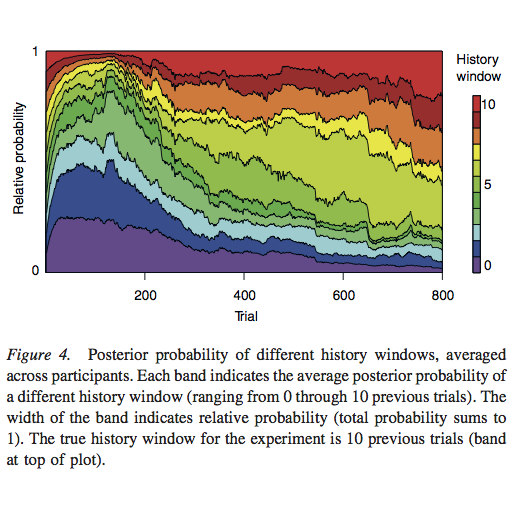

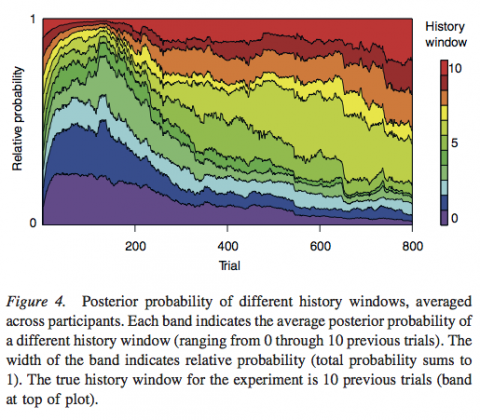

Melioration as rational choice: Sequential decision making in uncertain environments

Abstract: Melioration — defined as choosing a lesser, local gain over a greater longer term gain — is a behavioral tendency that people and pigeons share. As such, the empirical occurrence of meliorating behavior has frequently been interpreted as evidence that the mechanisms of human choice violate the norms of economic rationality. In some environments, the relationship between actions and outcomes is known. In this case, the rationality of choice behavior can be evaluated in terms of how successfully it maximizes utility given knowledge of the environmental contingencies. In most complex environments, however, the relationship between actions and future outcomes is uncertain and must be learned from experience. When the difficulty of this learning challenge is taken into account, it is not evident that melioration represents suboptimal choice behavior.

Paper: Feedback design for controlling a dynamic multitasking system

| If an organism is confronted with the problem of behaving approximately rationally, or adaptively, in a particular environment, the kinds of simplifications that are suitable may depend not only on the characteristics—sensory, neural, and other—of the organism, but equally on the nature of the environment. |

| H.A. Simon (1956), Rational choice and the structure of the environment, p. 130 |

Hansjörg Neth, Sangeet S. Khemlani, Wayne D. Gray

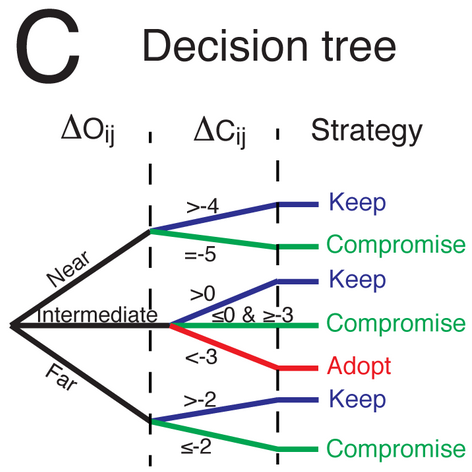

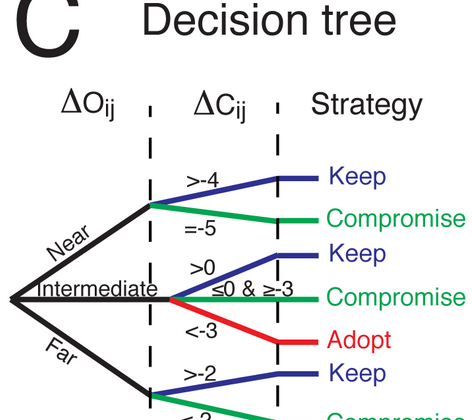

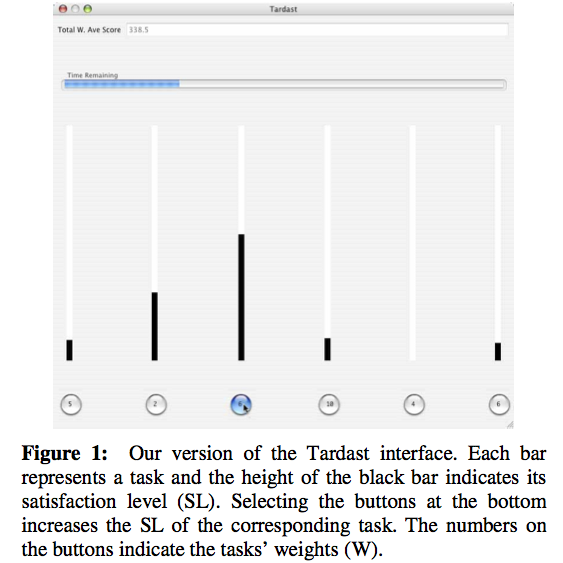

Feedback design for the control of a dynamic multitasking system: Dissociating outcome feedback from control feedback

Objective: We distinguish outcome feedback from control feedback to show that suboptimal performance in a dynamic multitasking system may be caused by limits inherent to the information provided rather than human resource limits.

Paper: Juggling multiple tasks in a synthetic task environment

| Doing two things at once, like singing while you take a shower, is not the same as instant messaging while writing a research report. Don’t fool yourself into thinking you can multitask jobs that need your full attention. You’re not really having a conversation while you write; you’re shifting your attention back and forth between the two activities quickly. You’re juggling. When you juggle tasks, your work suffers AND takes longer — because switching tasks costs. |

| Gina Trapani, Work Smart, FastCompany.com |

Hansjörg Neth, Sangeet S. Khemlani, Brittney Oppermann, Wayne D. Gray

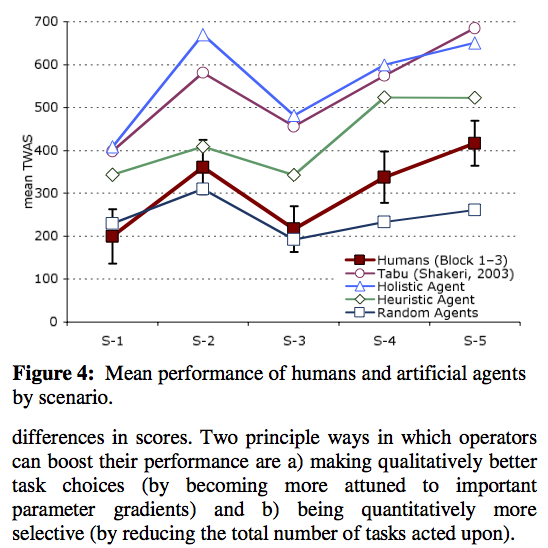

Juggling multiple tasks: A rational analysis of multitasking in a synthetic task environment

Abstract: Tardast (Shakeri 2003; Shakeri & Funk, in press) is a new and intriguing paradigm to investigate human multitasking behavior, complex system management, and supervisory control. We present a replication and extension of the original Tardast study that assesses operators’ learning curve and explains gains in performance in terms of increased sensitivity to task parameters and a superior ability of better operators to prioritize tasks. We then compare human performance profiles to various artificial software agents that provide benchmarks of optimal and baseline performance and illustrate the outcomes of simple heuristic strategies. Whereas it is not surprising that human operators fail to achieve an ideal criterion of performance, we demonstrate that humans also fall short of a principally achievable standard. Despite significant improvements with practice, Tardast operators exhibit stable sub-optimal performance in their time-to-task allocations.