Posts in Category: representation

representational effects (e.g., on arithmetic or logical thinking)

Paper: Arithmetic with Arabic vs. Roman numerals

| … how information is represented can greatly affect how easy it is to do different things with it. (…) it is easy to add, to subtract, and even to multiply if the Arabic or binary representations are used, but it is not at all easy to do these things — especially multiplication — with Roman numerals. This is a key reason why the Roman culture failed to develop mathematics in the way the earlier Arabic cultures had. |

| D Marr (1982): Vision, p. 21 |

Dirk Schlimm, Hansjörg Neth

Modeling ancient and modern arithmetic practices: Addition and multiplication with Arabic and Roman numerals

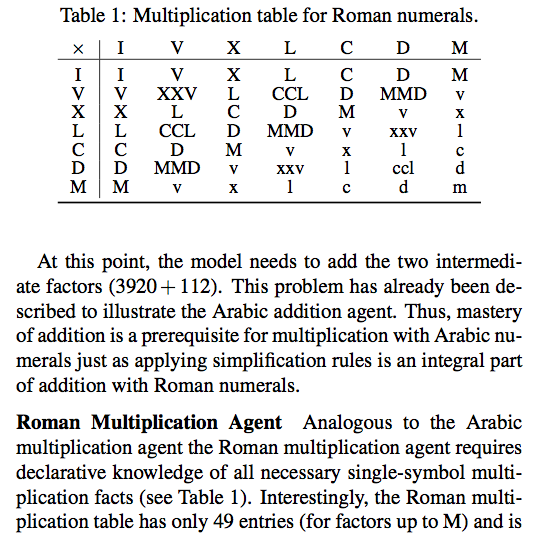

Abstract: To analyze the task of mental arithmetic with external representations in different number systems we model algorithms for addition and multiplication with Arabic and Roman numerals. This demonstrates that Roman numerals are not only informationally equivalent to Arabic ones but also computationally similar — a claim that is widely disputed. An analysis of our models’ elementary processing steps reveals intricate trade-offs between problem representation, algorithm, and interactive resources. Our simulations allow for a more nuanced view of the received wisdom on Roman numerals. While symbolic computation with Roman numerals requires fewer internal resources than with Arabic ones, the large number of needed symbols inflates the number of external processing steps.

Paper: Melioration dominates maximization

| There is no reason to suppose that most human beings are engaged in maximizing anything unless it be unhappiness, and even this with incomplete success. |

| R.H. Coase (1980), The Firm, the Market, and the Law, p. 4 |

Hansjörg Neth, Chris R. Sims, Wayne D. Gray

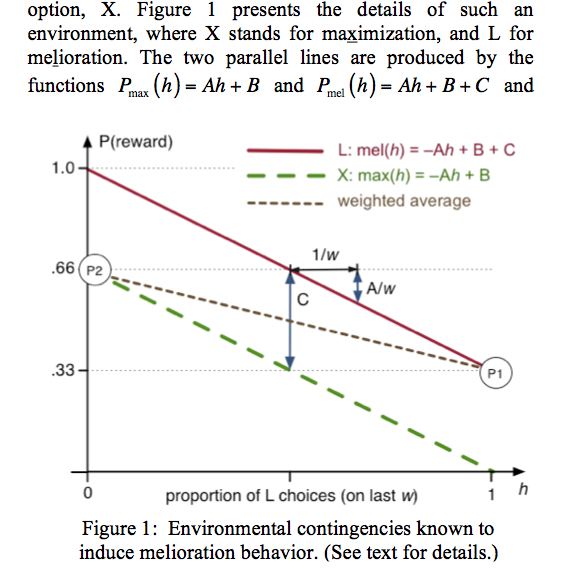

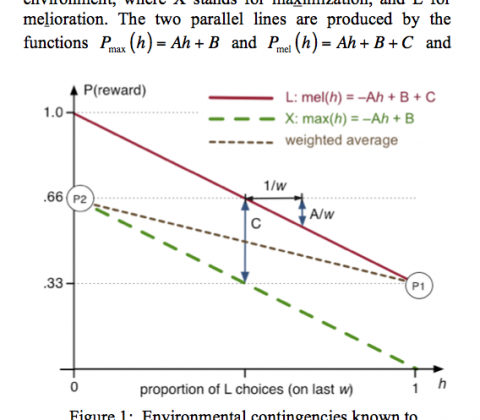

Melioration dominates maximization: Stable suboptimal performance despite global feedback

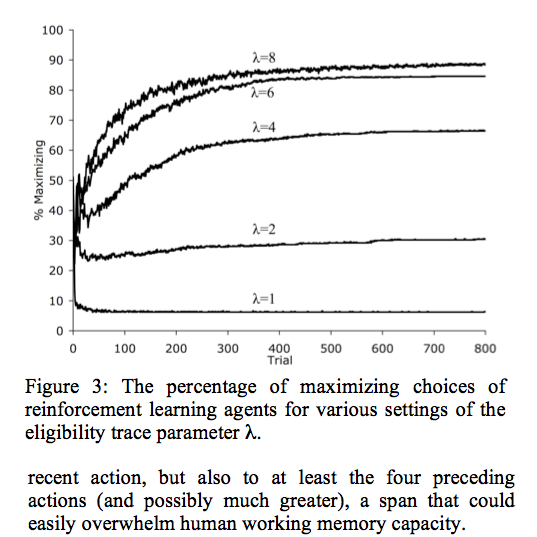

Abstract: Situations that present individuals with a conflict between local and global gains often evoke a behavioral pattern known as melioration — a preference for immediate rewards over higher long-term gains. Using a variant of a binary forced- choice paradigm by Tunney & Shanks (2002), we explored the potential role of global feedback as a means to reduce this bias.

Paper: Melioration despite informative feedback

| In many ways the word ‘meliorizing’ expresses a sensible middle way between optimizing and satisficing. Where optimus means best, melior means better. (…) Like a river, natural selection blindly meliorizes its way down successive lines of immediately available least resistance. The animal that results is not the most perfect design conceivable, nor is it merely good enough to scrape by. It is the product of a historical sequence of changes, each one of which represented, at best, the better of the alternatives that happened to be around at the time. |

| Richard Dawkins (1982), The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene, p. 46 |

Hansjörg Neth, Chris R. Sims, Wayne D. Gray

Melioration despite more information: The role of feedback frequency in stable suboptimal performance

Abstract: Situations that present individuals with a conflict between local and global gains often result in a behavioral pattern known as melioration — a preference for immediate rewards over higher long-term gains. Using a variant of a paradigm by Tunney & Shanks (2002), we explored the potential role of feedback as a means to reduce this bias. We hypothesized that frequent and informative feedback about optimal performance might be the key to enable people to overcome the documented tendency to meliorate when choices are rewarded probabilistically. Much to our surprise, this intuition turned out to be mistaken. Instead of maximizing, 19 out of 22 participants demonstrated a clear bias towards melioration, regardless of feedback condition. From a human factors perspective, our results suggest that even frequent normative feedback may be insufficient to overcome inefficient choice allocation. We discuss implications for the theoretical notion of rationality and provide suggestions for future research that might promote melioration as an explanatory mechanism in applied contexts.

Paper: simBorgs modeling dynamic decision making

| For the exogenously extended organizational complex functioning as an integrated homeostatic system unconsciously, we propose the term “cyborg”. |

| M.E. Clynes and N.S. Kline (1960), Cyborgs and Space (Astronautics, 13) |

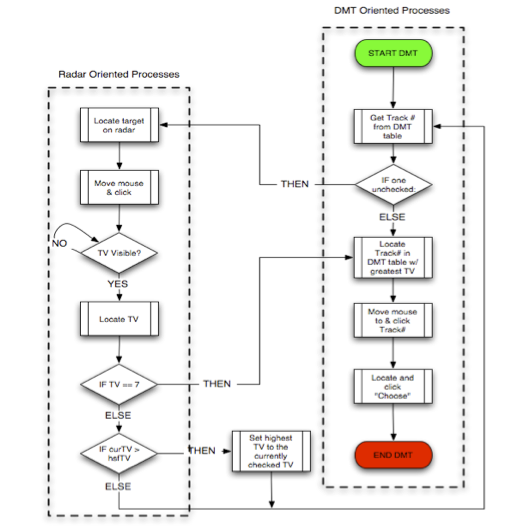

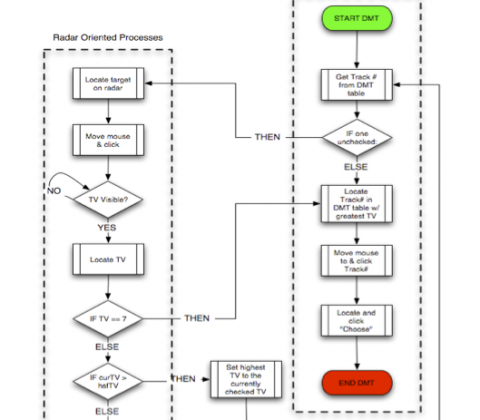

Christopher W. Myers, Hansjörg Neth, Michael J. Schoelles, Wayne D. Gray

The simBorg approach to modeling a dynamic decision-making task

Abstract: The simulated cyborg (or, simBorg) approach blends computational embodied-cognitive models of interactive behavior with artificial intelligence based components in a simulated task environment (Gray, Schoelles, & Veksler, 2004). simBorgs combine human and machine components. This combination of high fidelity cognitive modeling (human) and AI (machine) facilitates the development of families of models that allow the modeler to hold components (memory, vision, etc) at different levels of expertise without concern for cognitive plausibility. For example, rather than modeling human problem solving, the modeler can rely on various black-box techniques (i.e., cognitively implausible AI), thereby focusing on predicting how subtle differences in costs and benefits in interactive methods affect performance and errors. The current modeling endeavor adopts the simBorg approach in order to build a family of interactive decision-making agents.