Posts Tagged: PhD

Ph.D.-related posts and papers

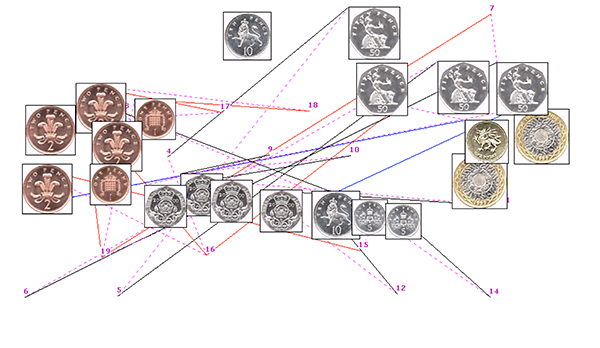

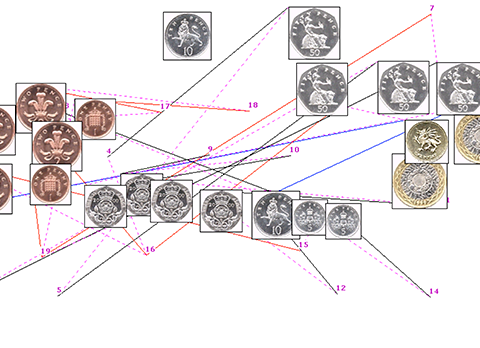

Paper: Interactive coin addition

| ‘Can you do Addition?’ the White Queen asked. ‘What’s one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one?’ ‘I don’t know,’ said Alice. ‘I lost count.’ |

| Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, Chapter IX. |

Hansjörg Neth, Stephen J. Payne

Interactive coin addition: How hands can help us think

Abstract: Does using our hands help us to add the value of a set of coins?

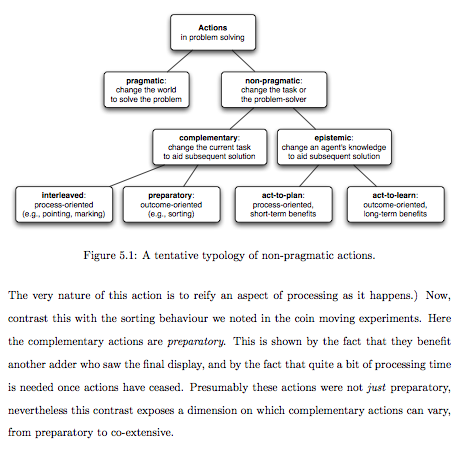

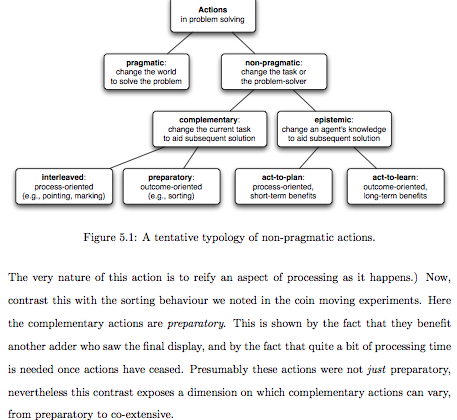

Paper: A taxonomy of (practical vs. theoretical) actions

| The solution to a problem changes the problem. |

| Peer’s Law |

Hansjörg Neth, Thomas Müller

Thinking by doing and doing by thinking: A taxonomy of actions

Abstract: Taking a lead from existing typologies of actions in the philosophical and cognitive science literatures, we present a novel taxonomy of actions.

Paper: Immediate interactive behavior (IIB)

| … immediate behavior, responses that must be made to some stimulus within very approximately one second (that is, roughly from ~300 ms to ~3 sec). (…) … immediate behavior is where the architecture shows through — where you can see the cognitive wheels turn and hear the cognitive gears grind. Immediate behavior is the appropriate arena in which to discover the nature of the cognitive architecture. |

| A. Newell (1990), Unified theories of cognition, p. 235f. |

Hansjörg Neth, Richard A. Carlson, Wayne D. Gray, Alex Kirlik, David Kirsh, Stephen J. Payne

Immediate interactive behavior: How embodied and embedded cognition uses and changes the world to achieve its goals

Summary: We rarely solve problems in our head alone. Instead, most real-world problem solving and routine behavior recruits external resources and achieves its goals through an intricate process of interaction with the physical environment. Immediate interactive behavior (IIB) entails all adaptive activities of agents that routinely and dynamically use their embodied and environmentally embedded nature to augment cognitive processes. IIB also characterizes an emerging domain of cognitive science research that studies how cognitive agents exploit and alter their task-environments in real-time. Examples of IIB include arranging coins when adding their values, solving a problem with paper and pencil, arranging tools and ingredients while preparing a meal, programming a VCR, and flying an airplane.

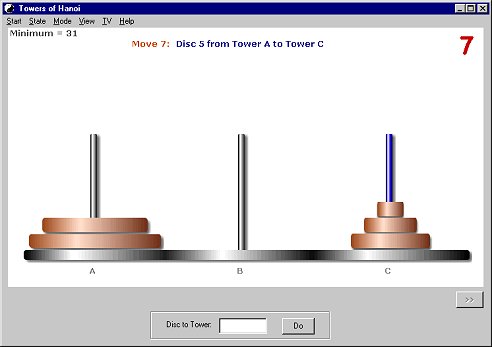

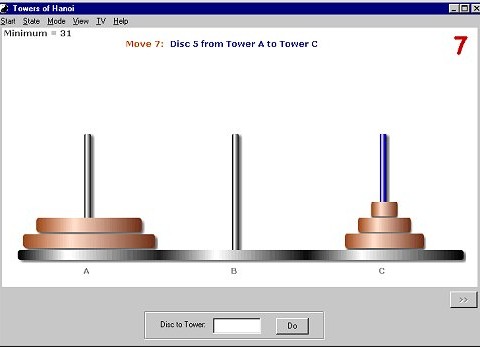

Paper: Thinking by doing?

| There is a co-ordination of senses and thought, and also a reciprocal influence between brain activity and material creative activity. In this reaction the hands are peculiarly important. It is a moot point whether the human hand created the human brain, or the brain created the hand. Certainly the connection is intimate and reciprocal. |

| A.N. Whitehead, Technical Education and its Relation to Science and Literature, p. 78. |

Hansjörg Neth, Stephen J. Payne

Thinking by doing? Epistemic actions in the tower of Hanoi

Abstract: This article explores the concept of epistemic actions in the Tower of Hanoi (ToH) problem. Epistemic actions (Kirsh & Maglio, 1994) are actions that do not traverse the problem space toward the goal but facilitate subsequent problem solving by changing the actor’s cognitive state. We report an experiment in which people repeatedly solve ToH tasks. An instructional manipulation asked participants to minimize moves either trial by trial or only on the last three of six trials. This manipulation did not have the predicted effect on the trial-by-trial move counts. A second, device manipulation provided some participants with an “exploratory mode” in which move sequences could be tried then undone without affecting the criterion move count. Participants effectively used this mode to reduce moves on each trial, but there was no clear evidence that they used it to learn about the problem across trials. We conclude that there is strong evidence for one sub-type of epistemic action (acting-to-plan) but no evidence for a second sub-type (acting-to-learn).