Posts in Category: abstract

published abstract

Paper: Immediate interactive behavior (IIB)

| … immediate behavior, responses that must be made to some stimulus within very approximately one second (that is, roughly from ~300 ms to ~3 sec). (…) … immediate behavior is where the architecture shows through — where you can see the cognitive wheels turn and hear the cognitive gears grind. Immediate behavior is the appropriate arena in which to discover the nature of the cognitive architecture. |

| A. Newell (1990), Unified theories of cognition, p. 235f. |

Hansjörg Neth, Richard A. Carlson, Wayne D. Gray, Alex Kirlik, David Kirsh, Stephen J. Payne

Immediate interactive behavior: How embodied and embedded cognition uses and changes the world to achieve its goals

Summary: We rarely solve problems in our head alone. Instead, most real-world problem solving and routine behavior recruits external resources and achieves its goals through an intricate process of interaction with the physical environment. Immediate interactive behavior (IIB) entails all adaptive activities of agents that routinely and dynamically use their embodied and environmentally embedded nature to augment cognitive processes. IIB also characterizes an emerging domain of cognitive science research that studies how cognitive agents exploit and alter their task-environments in real-time. Examples of IIB include arranging coins when adding their values, solving a problem with paper and pencil, arranging tools and ingredients while preparing a meal, programming a VCR, and flying an airplane.

Paper: Searching for counterexamples

| If it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be; but as it isn’t, it ain’t. That’s logic. |

| Tweedledee (Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass and what Alice found there, 1872) |

Hansjörg Neth, Philip N. Johnson-Laird

The search for counterexamples in human reasoning

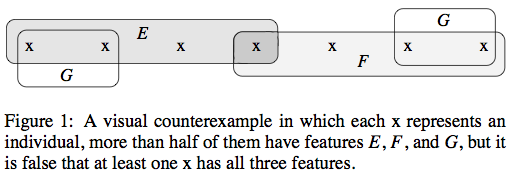

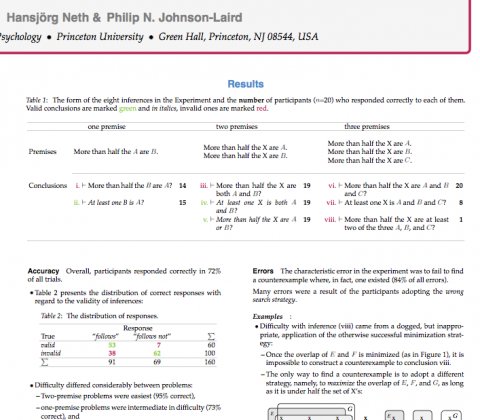

Research question: A major point of contention about human reasoning is whether or not individuals search for counterexamples to conclusions. According to theorists who argue that the mind is equipped with tacit rules of inference, the decision that an argument is invalid depends on a failure to find a derivation leading from the premises to the conclusion (see e.g., Rips, 1994). However, with this procedure, one can never be cer- tain that the space of possible derivations has been searched exhaustively. Alternatively, reasoners may base their inferences on mental models (Johnson-Laird and Byrne, 1991). This theoretical account rests on the semantic principle of validity: a conclusion is valid if and only if it allows for no counterexamples, i.e., possibilities in which the premises are true but the conclusion is false. Hence, by constructing a counterexample, reasoners are able to know that an inference is invalid.

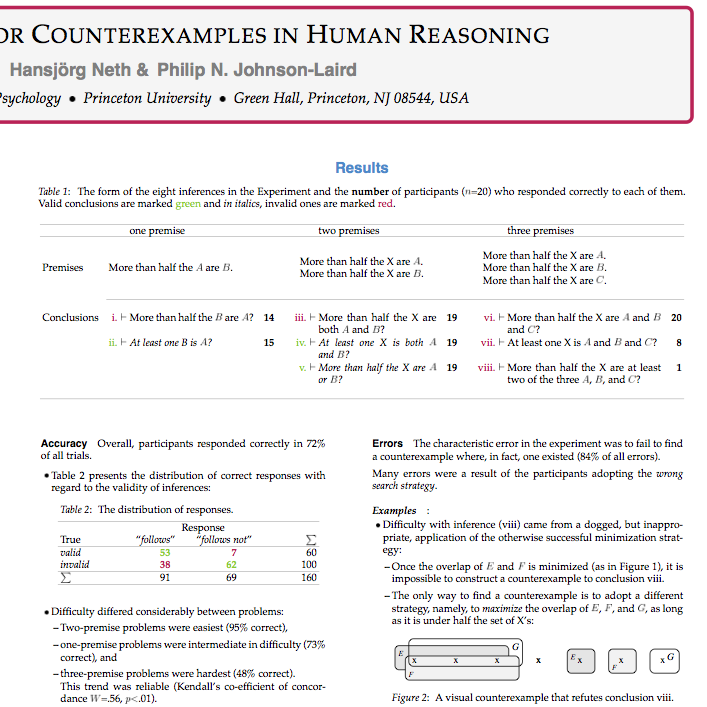

Method: To search for a search for counterexamples, we carried out an experiment in which the participants had to evaluate eight inferences based on non-standard quantifiers. Quite common in everyday life, such inferences call for a higher-order predicate calculus, which is incomplete.

Results: A striking phenomenon was the participants’ spontaneous use of a variety of strategies. In 80% of all trials, they constructed a single specific instance of the premises. Typically, the participants constructed a diagram in which they tried to minimize the overlap between the given sets. Indeed, every single participant came up with at least one counterexample. Our study has shown (…) that logically naive individuals do spontaneously search for counterexamples for at least one sort of deduction.

Keywords: Logic, thinking and reasoning, syllogisms with non-standard quantifiers, mental model theory, counterexamples.

Reference: Neth, H., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1999). The search for counterexamples in human reasoning. In M. Hahn, & S. C. Stoness (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (p. 806). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Related: Suppression effects | Diploma thesis

Resources: Download PDF | Google Scholar