Posts in Category: experiment

experimental and empirical research

Paper: Discretionary interleaving and cognitive foraging

| (…) we make search in our memory for a forgotten idea, just as we rummage our house for a lost object. In both cases we visit what seems to us the probable neighborhood of that which we miss. We turn over the things under which, or within which, or alongside of which, it may possibly be; and if it lies near them, it soon comes to view. |

| William James (1890), The Principles of Psychology, p. 654 |

Stephen J. Payne, Geoffrey B. Duggan, Hansjörg Neth

Discretionary task interleaving: Heuristics for time allocation in cognitive foraging

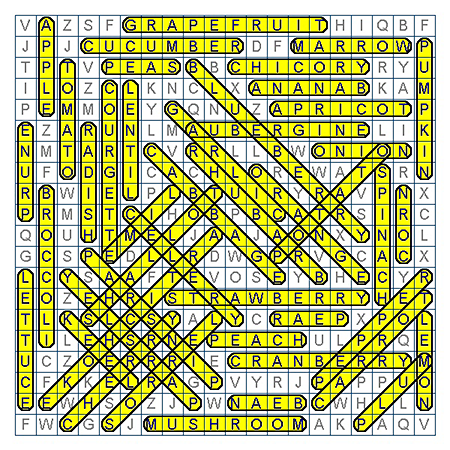

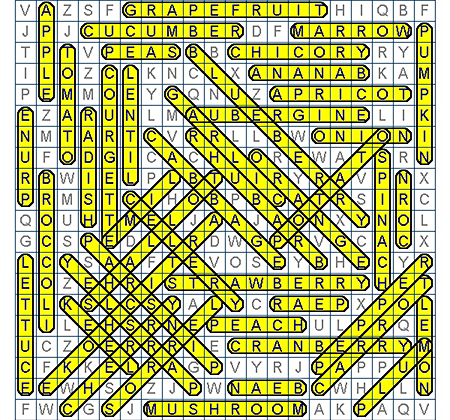

Abstract: When participants allocated time across 2 tasks (in which they generated as many words as possible from a fixed set of letters), they made frequent switches. This allowed them to allocate more time to the more productive task (i.e., the set of letters from which more words could be generated) even though times between the last word and the switch decision (“giving-up times”) were higher in the less productive task. These findings were reliable across 2 experiments using Scrabble tasks and 1 experiment using word-search puzzles. Switch decisions appeared relatively unaffected by the ease of the competing task or by explicit information about tasks’ potential gain. The authors propose that switch decisions reflected a dual orientation to the experimental tasks. First, there was a sensitivity to continuous rate of return — an information-foraging orientation that produced a tendency to switch in keeping with R. F. Green’s (1984) rule and a tendency to stay longer in more rewarding tasks. Second, there was a tendency to switch tasks after subgoal completion. A model combining these tendencies predicted all the reliable effects in the experimental data.

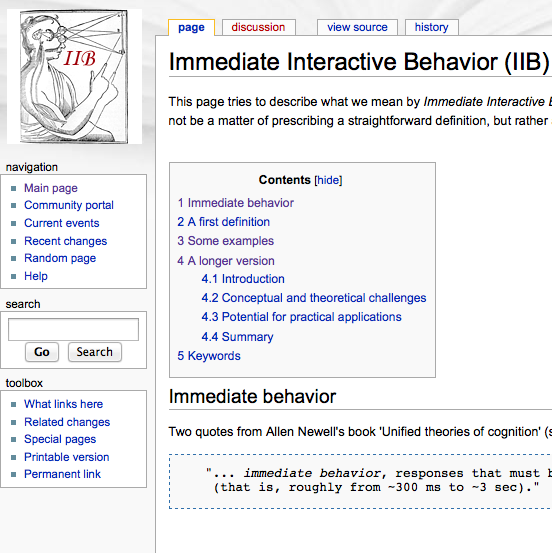

Paper: Immediate interactive behavior (IIB)

| … immediate behavior, responses that must be made to some stimulus within very approximately one second (that is, roughly from ~300 ms to ~3 sec). (…) … immediate behavior is where the architecture shows through — where you can see the cognitive wheels turn and hear the cognitive gears grind. Immediate behavior is the appropriate arena in which to discover the nature of the cognitive architecture. |

| A. Newell (1990), Unified theories of cognition, p. 235f. |

Hansjörg Neth, Richard A. Carlson, Wayne D. Gray, Alex Kirlik, David Kirsh, Stephen J. Payne

Immediate interactive behavior: How embodied and embedded cognition uses and changes the world to achieve its goals

Summary: We rarely solve problems in our head alone. Instead, most real-world problem solving and routine behavior recruits external resources and achieves its goals through an intricate process of interaction with the physical environment. Immediate interactive behavior (IIB) entails all adaptive activities of agents that routinely and dynamically use their embodied and environmentally embedded nature to augment cognitive processes. IIB also characterizes an emerging domain of cognitive science research that studies how cognitive agents exploit and alter their task-environments in real-time. Examples of IIB include arranging coins when adding their values, solving a problem with paper and pencil, arranging tools and ingredients while preparing a meal, programming a VCR, and flying an airplane.

Paper: Juggling multiple tasks in a synthetic task environment

| Doing two things at once, like singing while you take a shower, is not the same as instant messaging while writing a research report. Don’t fool yourself into thinking you can multitask jobs that need your full attention. You’re not really having a conversation while you write; you’re shifting your attention back and forth between the two activities quickly. You’re juggling. When you juggle tasks, your work suffers AND takes longer — because switching tasks costs. |

| Gina Trapani, Work Smart, FastCompany.com |

Hansjörg Neth, Sangeet S. Khemlani, Brittney Oppermann, Wayne D. Gray

Juggling multiple tasks: A rational analysis of multitasking in a synthetic task environment

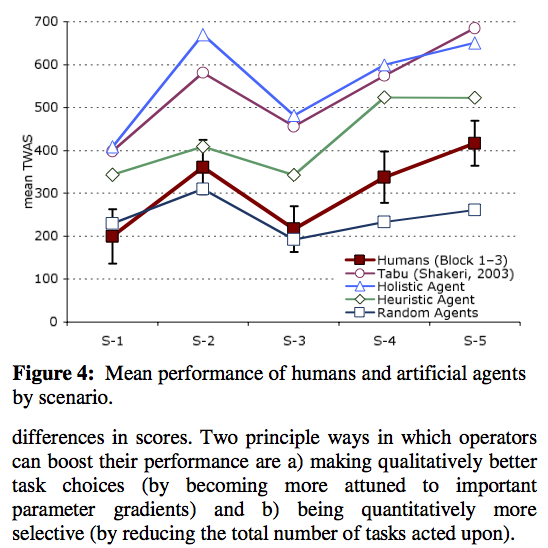

Abstract: Tardast (Shakeri 2003; Shakeri & Funk, in press) is a new and intriguing paradigm to investigate human multitasking behavior, complex system management, and supervisory control. We present a replication and extension of the original Tardast study that assesses operators’ learning curve and explains gains in performance in terms of increased sensitivity to task parameters and a superior ability of better operators to prioritize tasks. We then compare human performance profiles to various artificial software agents that provide benchmarks of optimal and baseline performance and illustrate the outcomes of simple heuristic strategies. Whereas it is not surprising that human operators fail to achieve an ideal criterion of performance, we demonstrate that humans also fall short of a principally achievable standard. Despite significant improvements with practice, Tardast operators exhibit stable sub-optimal performance in their time-to-task allocations.

Paper: Melioration dominates maximization

| There is no reason to suppose that most human beings are engaged in maximizing anything unless it be unhappiness, and even this with incomplete success. |

| R.H. Coase (1980), The Firm, the Market, and the Law, p. 4 |

Hansjörg Neth, Chris R. Sims, Wayne D. Gray

Melioration dominates maximization: Stable suboptimal performance despite global feedback

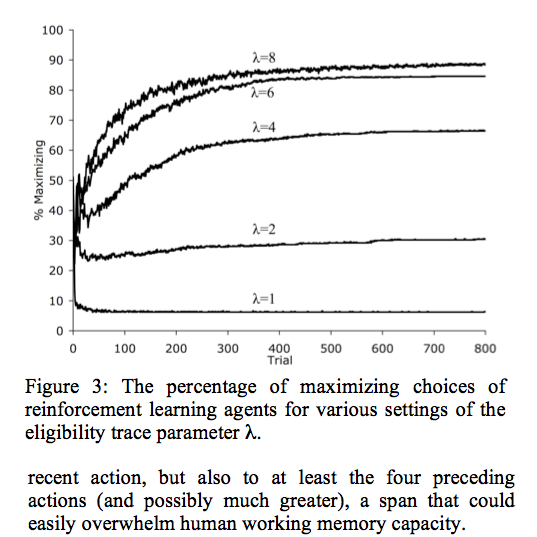

Abstract: Situations that present individuals with a conflict between local and global gains often evoke a behavioral pattern known as melioration — a preference for immediate rewards over higher long-term gains. Using a variant of a binary forced- choice paradigm by Tunney & Shanks (2002), we explored the potential role of global feedback as a means to reduce this bias.